The Political Ideas of Marx and Engels Review

Dear Reader, we make this and other manufactures available for costless online to serve those unable to beget or admission the print edition of Monthly Review. If you read the magazine online and tin beget a print subscription, we hope yous will consider purchasing ane. Please visit the MR store for subscription options. Thank you very much.

Engels vs. Marx?: 2 Hundred Years of Frederick Engels

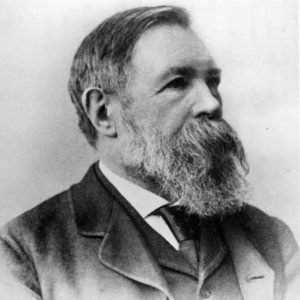

By William Elliott Debenham (1839-1924) - [ane], Public Domain, Link.

At the bicentenary of his birth, Frederick Engels's reputation every bit an original thinker is, amidst Anglophone academics at least, at its nadir. The main reason for this unfortunate situation is undoubtedly political. Despite the contempo global economical crunch and associated increases in inequality that have tended to ostend Karl Marx and Engels's general critique of commercialism, Marxism is an optimistic doctrine that has not fared well in a context dominated by working-class retreat and demoralization.1 But if this context has been unpropitious for Marxism generally, criticisms of Engels's idea accept a 2nd, quite separate, source. Over the course of the twentieth century, a growing number of commentators take claimed that Engels fundamentally distorted Marx's thought, and that "Marxism" and specially Stalinism emerged out of this ane-sided extravaganza of Marx's ideas.2

While the merits that Engels distorted Marx's ideas has roots going back to the nineteenth century, 1956 was a pivotal moment after which information technology increasingly became a dominant theme within the secondary literature.3 When a New Left emerged in response to Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech, the Russian invasion of Republic of hungary, and the Anglo-French-Israeli invasion of Egypt, information technology attempted to renew socialism through a critical reassessment of Marxism. Engels'south contribution to Marxism became a focal point in the ensuing debate. Though a small minority amid this milieu attempted to rescue Engels's and V. I. Lenin'due south reputations alongside that of Marx from any clan with Joseph Stalin's counterrevolution, a much larger grouping concluded that the experience of Stalinism damned the entire Marxist tradition all the way back to Marx. Between these two poles, a 3rd group counterposed Marx'due south youthful "humanistic" writings to Engels'southward "scientific" estimation of Marxism.4

Drawing on a one-sided interpretation of Georg Lukács's early disquisitional comments on Engels's concepts of a dialectics of nature, this milieu gravitated to the view that Engels was Marx's greatest mistake. Thus, by 1961, George Lichtheim could take it for granted that whereas Marx had sought to transcend the opposition betwixt idealism (autonomous morality) and materialism (heteronymous causation) through his concept of praxis, Engels had reduced Marxism to a positivistic class of materialism.five A few years subsequently, Donald Clark Hodges essentially endorsed the view among academics that "the young Marx has go the hero of Marx scholarship and the belatedly Engels its villain."6 Similarly, in 1968, Alasdair MacIntyre wrote of, and rejected, Engelsian Marxism for its apparent conception of revolution as a quasi-neutral event. Engels, co-ordinate to this critique, believed that "nosotros must expect the coming of the revolution as we look the coming of an eclipse."7

In what is probably the most uncharitable critique of Engels'south idea, Norman Levine argues that while it is true that Marxism gave rise to Stalinism, twentieth-century Marxism is best understood as a form of "Engelsism," a bastardization of Marx's original ideas in which his sublation of idealism and materialism was reduced to a positivist, mechanical, and fatalistic caricature of the real thing. "There was," according to Levine, "a articulate and steady evolution from Engels to Lenin to Stalin," and "Stalin carried this tradition of Engels and the Engelsian side of Lenin to its extreme."viii

The rational cadre of the merits that Engels begat Marxism derives from the fact that Engels penned the nearly influential popularization of his and Marx's ideas: the ironically titled Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science. Universally known equally Anti-Dühring, this book played a cardinal role in winning the leadership of the German Social Democratic Party to Marxism during the menstruation of Otto von Bismarck's antisocialist laws.9 Anti-Dühring is also Engels's about controversial work. This is in large role because, as Hal Draper has pointed out, it is "the only more or less systematic presentation of Marxism" written by either Marx or Engels. Consequently, anyone wanting to reinterpret Marx's thought must first disassemble this book from his seal of approval.10 It is thus around Anti-Dühring, the shorter excerpt from it, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, and other related works, most notably Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy and the unfinished and unpublished in his lifetime Dialectics of Nature, that debates about the relationship of Marx to "Engelsian" Marxism tend to turn.

In his contribution to this literature, John Holloway argues that while it would exist wrong to overemphasize the differences betwixt Marx and Engels, this is more than to the detriment of the former—particularly the Marx of the 1859 preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy—than it is to Engels'due south advantage. Co-ordinate to Holloway, "science, in the Engelsian tradition which became known as 'Marxism,' is understood equally the exclusion of subjectivity."11 If Holloway is honest enough to recognize that Marx's ideas cannot easily exist unpicked from those of Engels, Paul Thomas wants to spare Marx from the criticisms of Engels: "Engels's postal service-Marxian doctrines owe footling or nothing to the man he chosen his mentor."12 According to Thomas, the "conceptual chasm separating Marx's writings from the arguments fix forth in Anti-Dühring is such that fifty-fifty if Marx was familiar with these arguments, he disagreed with" Engels'southward view that "human beings…are in the last analysis physical objects whose motion is governed past the same general laws that regulate the move of all matter."xiii Terrell Carver has produced what is probably the most comprehensive version of the difference thesis. He argues that whereas Marx saw "science as an action important in engineering science and industry," Engels viewed "its importance for socialists in terms of a system of cognition, incorporating the causal laws of concrete science and taking them as a model for a covertly bookish written report of history, 'idea' and, somewhat implausibly, current politics."14

Like Thomas, Carver disapproves of this approach and believes it separates Engels from Marx. Carver explains Marx's indulgence toward these conflicting ideas in very disparaging terms: "perhaps he felt information technology was easier, in view of their long friendship, their office every bit leading socialists, and the usefulness of Engels's financial resources, to continue quiet and not interfere in Engels'due south work, even if it conflicted with his own."15 Unfortunately, or then Carver suggests, Marx'south silence about Anti-Dühring and related works immune Engels's thought to accept on the mantle of orthodoxy first inside the Second International before subsequently becoming "the footing of official philosophy and history in the Soviet Union."sixteen This was a disastrous turn of events, for Engels was either "unaware (or had he forgotten?)" that whereas The German Ideology had transcended the opposition between materialism and idealism, "his materialism…was close in many respects to existence a simple reversal of philosophical idealism and a faithful reflection of natural sciences as portrayed by positivists."17 In a nutshell, Carver, Holloway, Levine, Lichtheim, and Thomas are prominent proponents of what John Green calls a "new orthodoxy" that condemns Engels for having reduced Marx's conception of revolutionary praxis to a version of the mechanical materialism and political fatalism against which he and Marx had rebelled in the 1840s.eighteen

Superficially, at least, the claim that Engels's Anti-Dühring is a mechanically materialist and politically fatalist text is an odd complaint. Engels's engagement with Dühring was explicitly intended as a defense of revolutionary political practice against the latter's moralistic reformism—and no less an interventionist Marxist than Lenin described it as "a handbook for every class-conscious worker."19 More substantively, Engels's response to Dühring's criticism of Marx'due south deployment of Hegelian categories every bit a "nonsensical analogy borrowed from the religious sphere" included a articulate recapitulation of Marx's revolution in philosophy.20 Whereas Dühring claimed that Marx's apply of the term sublation to explain how something can be "both overcome and preserved" was an example of "Hegelian verbal jugglery," Engels insisted that this term helped Marx synthesize the partial truths of older forms of materialism and idealism into a whole that transcended the limitations of these before perspectives.21 In fact, the claim that Anti-Dühring represents a fundamental break with Marx's philosophy rests on an unconvincing caricature of Engels'southward arguments.22 Moreover, the related attempt to downplay the essential unity of Marx and Engels's idea cannot withstand critical scrutiny.

In the most detailed attempt to forcefulness a division between Marx and Engels, Carver claims that they neither spoke with ane voice in "perfect agreement" nor did they embrace a simple division of labor such that obvious differences between their two voices tin can be dismissed as natural consequences of their engagements with dissimilar subject matters.23 Carver insists that the myth of a "perfect partnership" was invented by Engels after Marx's decease to justify his own standing inside the international socialist movement, and that, contra this myth, evidence for collaboration betwixt the two friends is much less significant than is ordinarily supposed. He argues that Marx and Engels penned only three "major" joint works during their lifetimes, and of these The Holy Family included separately signed chapters while The Communist Manifesto was written by Marx alone after taking into consideration Engels's earlier drafts. Finally, The German Ideology remained unfinished and unpublished in their lifetimes and is in fact an opaque document that obscures more than than information technology reveals of their early on human relationship—Carver labels it an "apocryphal" text that, as a volume, "never took place." By contrast with the "perfect partnership" image, Carver claims that it was just after Marx'southward death that Engels sought to, and largely succeeded in, "revoicing Marx" in his own words.24

A problem with Carver'south estimation of the Marx-Engels relationship is signaled in Holloway's critique of Engels's thought noted earlier. As Holloway suggests, Marx, particularly the Marx of the 1859 preface, shared many of the assumptions that are typically associated with Engels'southward supposed distortion of his thought. A comparable signal, though from the opposite perspective, was made forty years ago past Sebastiano Timpanaro. He argued that "anybody who begins by representing Engels in the role of a banalizer and distorter of Marx'due south idea inevitably ends by finding many of Marx'due south own statements likewise 'Engelsian.'"25 Also, the all-time two existent studies of Engels'southward work, Stephen Rigby's Engels and the Formation of Marxism (1992) and Dill Hunley's The Life and Idea of Friedrich Engels (1991) both powerfully contribute to demolishing the deviation myth, simply exercise so by arguing that Marx shared many if non all of the flaws normally associated with Engels'south work. Rigby insists that "attempts to counterpose the views of Marx and Engels are essentially a strategy to forestall a confrontation with the problems which lie within Marx's works themselves."26 Meanwhile, Hunley concludes that "in virtually respects the two men fundamentally agreed with each other" and their writings share similar contradictions between more and less powerful themes.27 In outcome, Rigby and to a lesser extent Hunley conclude that Engels should not be seen as the autumn guy in the history of Marxism considering the defects associated with his ideas are also feature of Marx'due south thought.

Across the problem of the divergence thesis of the theoretical parallels between Marx'south and Engels's works, Carver's account of the actual extent of collaboration between Marx and Engels is difficult to square with what we know of their relationship. In the commencement instance, Carver'due south defense of the divergence thesis depends on something of a harbinger person argument. Exterior the quasi-religious ideologues of the old Soviet bloc, where Marx and Engels's relationship was rather absurdly described as a "perfect whole" in which a "coming together in mind and spirit…worked together in harmony for xl years," the "perfect agreement" thesis is uninteresting considering information technology is obviously untrue—and Engels certainly did not brand whatsoever such merits.28 Any reasonable endeavour to reaffirm the uniquely close bond betwixt Marx and Engels from the 1840s until Marx's death in 1883 in no fashion implies that there were no disagreements or fallouts nor differences in tone, emphasis, and even substance across their writings over this period. Not merely would information technology be utterly bizarre if in that location were no such differences, just it is possible to locate such differences internal to the works of both Marx and Engels themselves (and to the works of whatsoever other interesting thinker!).

2d, Carver is wrong to dismiss the importance of the intellectual partition of labor that undoubtedly characterized Marx and Engels's relationship. It is a fact that Engels tended, every bit Draper points out in his superb study of Marx and Engels'southward politics, to handle "popularised expositions, 'party' issues, and certain subjects in which he was particularly interested or expert."29 And while it is truthful that this partition of labor betwixt the two founders of the Marxist tradition was in no sense accented, once properly understood, this fact actually serves to reinforce the claim of a high degree of collaboration between the two men. The all-encompassing correspondence betwixt them, especially in the period when Engels worked in Manchester while Marx lived in London (before and after this separation, they had much more opportunity simply to talk to each other), evidences a profound intellectual dialogue over a vast range of subjects from which both learned and through which they both honed their arguments.

Third, the division of labor betwixt these two friends reflected the fact that Engels was the intellectually stronger of the two men in a number of areas. In the 1970s, Perry Anderson rightly challenged the already "stylish" tendency "to depreciate the relative contribution of Engels to the cosmos of historical materialism" by making the "scandalous" but nonetheless valid point that "Engels'due south historical judgements are nearly always superior to those of Marx. He possessed a deeper knowledge of European history, and had a surer grasp of its successive and salient structures." Anderson was well aware of the "supremacy of Marx's overall contribution to the general theory of historical materialism," merely was justifiably keen to altitude himself from the typically rough criticisms associated with the anti-Engels literature.30

4th, Carver's assessment of the degree of formal collaboration between Marx and Engels is simply disingenuous. Likewise the three "major" works he mentions in his word of their supposed noncollaboration, Marx and Engels coauthored numerous of import, theoretically informed political interventions throughout their lives. They also corresponded on numerous bug, and readers of their correspondence can often find Engels'due south influence on subsequent texts written by Marx.31 It is typical that i of Marx's most famous aphorisms about history repeating itself, "the first fourth dimension equally tragedy, the 2nd as farce," was borrowed from Engels, while much of the substance, for case, of Marx's justly famous Critique of the Gotha Programme drew on similar arguments put along previously by Engels.32 Indeed, once we take seriously their joint political writings alongside their voluminous correspondence, it speedily becomes obvious just how implausible is Carver's proposition that their common projection was Engels'south invention.

The closest thing to hard testify for Marx's corroboration of the divergence thesis is a jokey letter he wrote to Engels on August 1, 1856. Carver emphasizes how, in this letter of the alphabet, Marx complains about a journalist writing of the 2 of them as if they were one.33 The writer in question was Ludwig Simon, an émigré deputy from the Frankfurt Associates of 1848–49, who exhibited what Marx called an "exceedingly odd" tendency "to speak of us in the singular—'Marx and Engels says' etc." Now, outside of a cowritten text, this phrase is by any mensurate a grammatical oddity. Nonetheless, in joking about Simon'south badly written "jeremiad"—Marx wrote to his old friend that he would "sooner swill soap-suds or hobnob with Zoroaster over mulled cow's piss than read through all that stuff"—Marx actually wrote of jokes that Engels had made during the revolution as if they belonged to the 2 of them "in the singular": "Even the jokes we cracked about Switzerland in the Revue 'make full him with indignation.'"34

Despite Carver'south claim that Marx "says zip positive" in this letter "or elsewhere at any length virtually the parameters of separation and overlap between" himself and Engels, the fact is that Marx repeatedly used the terms us, our, and we when referring to his political and theoretical relationship with Engels. And while his comments on this relationship may non accept been written "at length," the extant testify overwhelmingly supports the merits that Marx believed that he and Engels had a unique intellectual and political partnership. Perhaps his about famous annotate on the importance of his collaboration with Engels is to exist establish in his 1859 preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy:

Frederick Engels, with whom I maintained a constant exchange of ideas by correspondence since the publication of his brilliant essay on the critique of economic categories…arrived by another road (compare his Condition of the Working-Form in England) at the aforementioned consequence as I, and when in the spring of 1845 he too came to alive in Brussels, nosotros decided to set along together our formulation as opposed to the ideological one of High german philosophy, in fact to settle accounts with our former philosophical conscience.35

A twelvemonth later, November 22, 1860, he reaffirmed and indeed strengthened this claim in a letter of the alphabet to Bertalan Szemere in which he insisted that Engels "must" exist considered "my change ego." As to Engels's intellectual abilities, Marx wrote to Adolf Cuss, Oct 18, 1853, that "being a veritable walking encyclopaedia," Engels is "capable, drunkard or sober, of working at any 60 minutes of the day or nighttime, [he] is a fast writer and devilish QUICK in the uptake."36

For her part, Marx'southward daughter Eleanor wrote that her begetter used to talk to Engels's letters "every bit though the writer were there," agreeing, disagreeing, and sometimes laughing "until tears ran downwards his cheeks." And of their friendship she wrote, "it was 1 which will become as historical as that of Damon and Pythias in Greek mythology."37 Similarly, Marx's son-in-law Paul Lafargue reminisced that Marx "esteemed [Engels] every bit the most learned man in Europe" and "never tired of admiring the universality of his mind."38 In fact, contra Carver's baseless and frankly defamatory suggestion that Marx kept quiet near his criticisms of Engels'southward work because of the "usefulness of Engels'due south fiscal resources," it is unimaginable that anyone but "the nigh learned man in Europe" and, abreast that, one of the greatest revolutionary activists of the historic period, could maintain an equal partnership with a man of Marx'south stature for some four decades. Equally Chris Arthur writes, attempts to downplay Engels's influence on Marx are as unfair to Marx equally they are to Engels: "Marx was never one to judge lightly the intellectual deficiencies of others, however of all his contemporaries it was with Engels he chose to class a close intellectual partnership."39

Marx's appreciation of the importance of his collaboration with Engels was reaffirmed in his largely forgotten volume Herr Vogt (1860). In a comment on Engels's Po and Rhine, which, Marx wrote, was published "with my understanding" and which he described as providing a "scientific"—nasty Engelsian word this—"war machine proof that 'Germany does not need whatsoever part of Italy for its defence,'" he wrote that he and Engels mostly "work[ed] to a common plan and after prior agreement."40 Despite the facts that this unambiguous statement was fabricated in print, and that it was highlighted by Draper in Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, it tends to be ignored by those who aim to strength divisions betwixt Marx and Engels.41

Nor did Marx'south favorable comments on his collaboration with Engels end in 1860. Seventeen years later on, on November 10, 1877, in a letter to Wilhelm Blos, he wrote of "Engels and I" and "the states" when reviewing earlier political positions they had previously taken together.42 More than importantly, in a letter of the alphabet to Adolph Sorge dated September 19, 1879—written soon later on the publication of Anti-Dühring and less than 4 years before his ain death—Marx evidences the profound degree of collaboration between him and Engels. He wrote non simply of making "provision" that Engels have care of "concern matters and commissions" while he had been away on holiday, but also of Engels writing the now famous 1879 Circular Alphabetic character to the leadership of the German Social Democratic Political party in both of their names and in which "our signal of view is evidently prepare forth." Meanwhile, he wrote of "our attitude," "our back up," "we maintain," "Engels and I," "our complaint," "we differ from [Johan] Most," "our names," and against attempts to "rope us in" to supporting dissimilar positions with which they disagreed. All of this while praising Engels's rebuttal, from their shared point of view, of reformist "partisans of 'peaceable' development." Engels, he wrote, "showed how deep was the gulf between [Höchberg—PB] and u.s." by giving him a "piece of his heed."43

This letter of the alphabet and many others like it indicate that while it might exist foolish to care for Marx and Engels in the singular, it is much more cool to claim, as does Thomas, that "there is no evidence for whatever joint doctrine exterior of Engels's insistence that it was somehow—or had to be—'there.'"44 This is simply untrue, and Thomas's deprival of evidence from Marx for a joint doctrine with Engels suggests his research suffers from a problem he is eager to ascribe to others: "an astonishing ignorance of what Marx had written."45

Of course, Thomas is not ignorant of what Marx had written. But why and so continue to insist on the divergence thesis when the extant prove, every bit Hunley points out, "should demonstrate to anyone not utterly blinded by credo that Marx and Engels basically agreed with each other"?46 Information technology does seem that the proponents of the divergence thesis are motivated more by ideology than past testify. Indeed, Carver and Thomas argue not merely (and justifiably) that Marx's legacy should be disassociated from the inheritance of Stalinism but also (and unjustifiably) that it should similarly be disassociated from modernistic revolutionary politics.47 Tom Rockmore'due south anti-Engelsian position is different from Carver's and Thomas's because he accepts that "Marx and Engels concord[d] politically," while insisting that they "disagree[d] philosophically."48 Rockmore's argument benefits from recognizing, contra Carver'south claim that Marx conceived the transition to socialism through "constitutional" and "peaceful" ways, that Engels was right when he said in his eulogy to Marx that his collaborator was "above else a revolutionist."49 Nonetheless, Rockmore is wrong about Marx and Engels's supposed philosophical disagreements.

Engels's own assessment of his part in the formulation of the theoretical foundation of their political perspective is famously, and disproportionately, self-deprecating. A year after Marx'south death he claimed in a letter to Johann Philipp Becker, August 15, 1884, to accept been but "second fiddle" to Marx:

My misfortune is that since we lost Marx I have been supposed to represent him. I accept spent a lifetime doing what I was fitted for, namely playing second fiddle, and indeed I believe I acquitted myself reasonably well. And I was happy to have and then excellent a first fiddle as Marx. But now that I am suddenly expected to take Marx'south place in matters of theory and play first fiddle, at that place will inevitably exist blunders and no ane is more than enlightened of that than I. And non until the times become somewhat more turbulent shall we really exist aware of what we take lost in Marx. Not one of united states of america possesses the breadth of vision that enabled him, at the very moment when rapid action was chosen for, invariably to hit upon the right solution and at once go to the heart of the matter. In more peaceful times it could happen that events proved me right and him incorrect, but at a revolutionary juncture his judgement was virtually infallible.50

Iv years afterwards in Ludwig Feuerbach and the Terminate of Classical German Philosophy, he elaborated on this pocket-size appreciation of his contribution in impress:

Lately repeated reference has been made to my share in this theory, so I tin can hardly avoid saying a few words here to settle this point. I cannot deny that both earlier and during my forty years' collaboration with Marx I had a sure independent share in laying the foundations of the theory, and more specially in its elaboration. Simply the greater role of its leading basic principles, specially in the realm of economic science and history, and, above all, their final trenchant formulation, belongs to Marx. What I contributed—at any rate with the exception of my work in a few special fields—Marx could very well have done without me. What Marx accomplished I would not accept achieved. Marx stood higher, saw further, and took a wider and quicker view than all the rest of u.s.. Marx was a genius; we others were at best talented. Without him the theory would not be by far what it is today. It therefore rightly bears his name.51

It would, of grade, be foolish to deny Marx'due south greater part in his collaboration with Engels. Merely this fact is hardly surprising given that even in his youth one of his contemporaries, Moses Hess, felt justified in describing Marx thus:

He is a phenomenon…the greatest—perhaps the only genuine—philosopher of the current generation. When he makes a public appearance, whether in writing or in the lecture hall, he will attract the attending of all Deutschland.… He volition requite medieval religion and philosophy their insurrection de grâce; he combines the deepest philosophical seriousness with the about biting wit. Imagine Rousseau, Voltaire, Holbach, Lessing, Heine and Hegel fused into one person—I say fused not juxtaposed—and you have Dr Marx.52

To say that Engels (or anyone other than a latter-day Aristotle) failed to match the intellectual level of someone who could reasonably be described in these terms is not peculiarly illuminating. It is much more than interesting to recognize, with Anderson, that Engels had pregnant intellectual strengths and that he made a number of of import contributions to his and Marx'due south joint theoretical perspective.

Indeed, Marx was the beginning to recognize Engels'south strengths and to disabuse him of his uncalled-for humility. For instance, in a letter of July 4, 1864, he wrote: "Equally yous know. Beginning, I'1000 always belatedly off the mark with everything, and 2d, I inevitably follow in your footsteps."53 This assertion was especially true in the 1840s when Engels played not merely an important simply also a leading function in their intellectual and political partnership. Thereafter, the two men worked closely together in a collaboration through which each learned from the other and both became considerably more than they would have been had they simply worked lonely.

The departure thesis, past contrast, tends to make far also much of relatively pocket-sized differences between the two men and, at worst, to invent differences where they do not exist to adapt the particular predilections of each critic. Commenting on Levine's variant of this argument, Alvin Gouldner writes that "it is typical of Levine…that his formulations are not merely inexact but ludicrous."54 He adds that the idea that Engels initiated the vulgarization of Marx'south ideas continues to concur sway "less because of its intellectual justification than because of the demand it serves": the divergence myth effectively allows critics of Marxism to lay blame on Engels for whatever attribute of classical Marxism they want to turn down.55 In effect, this approach has informed a tendency to reimagine Engels, as Edward Thompson put it, every bit the "whipping male child" who has been saddled with any defect "that 1 chooses to impugn to subsequent Marxism."56 Notwithstanding, the anti-Engels literature is largely negative in scope and far from coherent. Because Engels'south critics generally dump onto him whichever part of Marxism they dislike, they are inclined, as Hunley points out, to contradict "one some other and sometimes fifty-fifty themselves."57 More than to the point, what Arthur calls the Engels-phobic literature tends to exist so nifty to denounce Engels that authors of this persuasion skirt over significant problems with their own arguments.58

This criticism is particularly true of attempts by Engels's critics to testify some degree of coherence between his views and Stalin'southward debased version of Marxism. Carver and Thomas, for instance, share Levine's belief that Stalin's ideology tin can be derived from "Engelsism." As Carver wrote in 1981, "political and academic life in the official institutions of the Soviet Union…involves a positive commitment to dialectical and historical materialism that derives from Engels's work but requires the posthumous imprimatur of Marx."59 A couple of years later, he wrote that "the tenets" of Engels's philosophical works were "passed on lectures, primers and handbooks, down to official Soviet dialectics."lx However, though information technology has ofttimes been repeated that Stalin's estimation of historical and dialectical materialism (Histmat and Diamat, equally they became known in the Soviet Spousal relationship) derived from Engels's work, it is less oft noted that Stalin's attempt to legitimize his counterrevolutionary government by reference to Marxism and the October Revolution led him to gut Marx and Engels's idea of its revolutionary essence.

In respect to Engels'due south thought, Stalin explicitly rejected a number of key ideas that derived from his work. He expunged from official Soviet theory Engels'south critique of the idea of socialism in one land, his view that socialism would exist characterized by the withering away of the state, and his claim that the law of value would cease to operate in a socialist society. In relation to philosophy, Stalin removed the concept of the "negation of the negation" from the account of dialectics that became orthodoxy in Russian federation in the 1930s.61 These parts of Engels's thought were non insubstantial aspects of his Marxism. As Alfred Evans points out in a merits that sits ironically beside the attempts past Carver and others to wrench Marx from Marxism so as to reimagine him equally a theorist of constitutional and peaceful change, Stalin's "innovations" underpinned a reinterpretation of Marxism from which "any revolutionary implications for socialist development" was severed.62 Stalin also acted to reify the historical schema presented in Marx'due south 1859 preface of his Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy so as to exclude from orthodoxy Marx and Engels'southward concept of an "Asiatic mode of product," through which they had aimed to make sense of oppressive class relations in societies without private property relations and which might easily be deployed to illuminate class relations in Soviet Russian federation.63 If the political reasoning behind this conclusion is obvious enough, the fact that, as he attempted to justify the function of the state in Soviet economical development, Stalin however felt compelled to invert Marx'south account of the relationship between base and superstructure, as outlined in this famous essay, illuminates how he revised Marx and Engels'southward thought non as part of a healthy developing tradition of inquiry merely through the incoherent demands associated with the more than mundane task of justifying the socialist credentials of "a nonsocialist lodge."64

As it happens, not only is Engels's thought incompatible with Stalinist ideology, but his ideas can be and take been profitably mined to make sense of the counterrevolutionary essence of Stalinism.65 In this sense at least, Stalin's revisions of Marxism reflect his better understanding of the disquisitional and revolutionary implications of Engels's idea than is evident in the work of many of the anti-Engels faction: it is precisely considering Engels's ideas were so critical and revolutionary that they were incompatible with Stalin's dictatorship. And if the revolutionary essence of Engels's thought helps explicate why Stalin aimed to neuter his Marxism, the anti-Stalinist implications of his work are good reason why modern socialists should seek an honest reassessment of his contribution to social and political theory.

A similar point could be made in relation to Engels's much-maligned concept of a dialectics of nature. Since the publication of Lukács'southward History and Class Consciousness in 1923, a defining characteristic of the Western Marxist tradition has included a rejection of Engels's effort to root Marxist theory in a dialectical understanding of nature.66

In History and Class Consciousness, Lukács suggested that Engels'southward unfortunate extension of the concept of dialectics from the social to the natural realms led him to ignore the "virtually vital interaction, namely the dialectical relation between bailiwick and object in the historical process," without which "dialectics ceases to exist revolutionary."67 Interestingly, though Lukács'due south critique of Engels's thought has had a very strong influence on the anti-Engels literature, it is somewhat brief, amounting to no more than a passing comment supported past a twelve-line footnote. Likewise, this comment was balanced by other comments in the text that seemed much more than uniform with Engels's arguments, for instance, where he wrote of "the necessity of separating the merely objective dialectics of nature from those of society."68 As information technology happens, within a couple of years of the publication of History and Class Consciousness, Lukács did write much more substantially, and much more positively, nearly the idea of a dialectic in nature:69

Self-evidently the dialectic could non possibly be effective as an objective principle of development of society, if information technology were not already constructive as a principle of development of nature before society, if it did non already objectively exist. From that, even so, follows neither that social development could produce no new, every bit objective forms of movement, dialectical movements, nor that dialectical movements in the development of nature would be knowable without the mediation of the new social dialectical forms.seventy

This passage is prove that Lukács connected to reject philosophical reductionism, without collapsing, every bit Antonio Gramsci and Karl Korsch had warned was a possible event of rejecting the dialectic of nature, into "the opposite error…a form of idealism."71 Unfortunately, while Lukács, Gramsci, and Korsch differentiated between reductive and nonreductive interpretations of Engels'south idea of a dialectic of nature, Engels'southward modernistic critics tend to be determined that the concept of a dialectics of nature lends itself inevitably to mechanical materialism and positivism.

John Bellamy Foster has argued that this critique of Engels emerged out of a one-sided interpretation of what he calls the "Lukács problem." Whereas Lukács, in History and Class Consciousness, incoherently combined a denial that the dialectical method is applicable to nature considering of the missing subjective dimension with a recognition of the beingness of a distinct, objective, dialectics in nature, Western Marxism has tended simply to deny the existence of a dialectic in nature.72 This claim non only contradicts what we know of Marx'southward by and large supportive comments on Engels'southward work on the dialectics of nature, but it also underpins a stiff trend toward forms of philosophical idealism. Consequently, rather than explore Marx'due south work for tools to assist exculpate Marxism from the twin pitfalls of mechanical materialism on the one side and philosophical idealism on the other, Western Marxists accept tended to lend their support to the projection of driving a wedge between an idealist estimation of Marx and a mechanically materialist estimation of Engels.73

By contrast with this approach, Foster, following Andrew Feenberg and Alfred Schmidt, has detailed how, through the concept of sensuous homo activity, Marx'due south work provides the necessary tools to make sense of the dialectical relationship betwixt nature and gild. According to Foster, Marx's materialism assumes what he calls a course of "natural praxis" through which human sensuous practice is understood to be embodied in the sensuous world itself. Our perceptions of the world are rooted in our natural senses, just, contra empiricism, the senses through which nature becomes aware of itself are not merely passive recipients of information from the external world, merely are agile and developing processes within the natural world whose evolution continues and deepens through humanity'due south productive interaction with nature. Foster insists that the concept of natural praxis is compatible with Engels'southward emergentist conception of reality while avoiding the pitfalls of reductionist readings of Engels's piece of work.74

Moreover, and much more interestingly, he argues that this conception of praxis coheres with gimmicky ecological concerns. Prefiguring mod ecology's business organization with humanity'south oneness with nature, Engels'southward formulation of a dialectics of nature opens a space through which ecological crises could be understood in relation to alienated nature of capitalist social relations. Because production is beginning and foremost a metabolic exchange with nature, alienated relations of production include an alienated relationship to nature itself. Consequently, the same forces that underpin capitalism's tendency toward economic crises generate parallel tendencies toward environmental crises. Marx and Engels's understanding of the unity of humanity and nature is thus suggestive of a revolutionary perspective that is simultaneously political, social, and ecological in scope: the socialist revolution would involve not merely a transformation of social and political relations, information technology would also necessarily involve a radical transformation of humanity'south human relationship to nature. The internal human relationship betwixt capitalist and ecological crises informs Foster'due south argument that Engels's merits that "nature is the proof of dialectics" can and should be revised to read that "environmental" has become "the proof of dialectics."75 And so, whereas Engels's critics take tended to reimagine Marx as merely a social theorist, Engels's philosophical writings illuminate the powerful ecological dimension of his and Marx's thought, and consequently the internal link between ecological concerns and anticapitalism.

Foster'due south statement powerfully illuminates my contention that it would be a grievous fault to lose sight of Engels'southward fundamental, overwhelmingly positive and nonetheless relevant contribution to socialist theory and practice. His thought shares the central strengths of Marx's work, whose themes he often prefigured, while he made powerful and independent contributions to Marxism in his own right. And it is my belief that the left would benefit enormously from a serious reassessment of his piece of work.

Alongside Marx, Engels worked a revolution in theory: the ii of them famously synthesized French socialism, German philosophy, and English political economy into a new revolutionary perspective on society. This genuinely collaborative project was forged through the odd medium of a fragmentary manuscript that remained unpublished in their lifetimes and that has come up down to posterity as The German Credo. Though this text is problematic, its production nonetheless represents, as Marx wrote and Engels reiterated, a central moment of "self-clarification" through which their subsequent theoretical and practical project was framed. Commenting on this period in their lives, Korsch writes:

Marx and Engels during the side by side 2 years worked out in item the contrast prevailing between their own materialist and scientific views and the various ideological standpoints represented by their sometime friends amid the left Hegelians (Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Max Stirner) and by the philosophical belles-lettres of the "German" or "true" socialists.76

By contrast with both Marx'southward and Engels'south retrospective assessments of the significance of the moment when they wrote the manuscripts that have come down to united states of america every bit The German Ideology, it is a characteristic of the anti-Engels literature to endeavour to downplay the extent to which these manuscripts prove a pivotal moment in the process of their intellectual cocky-clarification.77

One problem with this line of argument is that fifty-fifty though The High german Ideology never existed as a proposed book, Marx and Engels did work up their ideas into a course that they attempted to have published in 1845–46.78 And as Carver himself has pointed out, the sketch of Marx's method outlined in his 1859 preface closely follows the language of the chapter on Feuerbach in The German Ideology.79 More to the point, Arthur argues that all the insights from their before writings are synthesized in these manuscripts through the thought that people make and remake themselves through their social and productive interaction with nature to come across their evolving needs.fourscore This perspective was both rooted in and oriented toward the new proletarian course of social practice, and as a philosophy of praxis it was start tested and deepened through a remarkable political intervention into the revolutionary events of 1848–49.

The decade of the 1840s was a moment of great democratic expectation when the mismatch between Europe's existing institutions of power on the one hand and the new social reality of burgeoning capitalist development on the other informed a growing sense of radical modify across the continent.81 If the defeat of this movement occasioned Marx and Engels's systematic reflections on their own applied and theoretical contributions to the movement, their subsequent work is best understood as extending and deepening the arroyo they forged in the 1840s: 1848 became the touchstone for everything else they wrote and did.82 Later on, their unique and profound collaboration remained undiminished up until Marx'southward death in 1883, after which Engels continued their projection both through his ain political and theoretical works and by preparing for (re)publication a number of Marx's writings including, nearly importantly (and controversially), the second and third volumes of Capital.83

If the fundamentals of Marx and Engels's strategy were forged collaboratively in the mid–1840s, Engels was already moving in the direction of their articulation projection earlier he met Marx and he subsequently made independent and of import contributions to their collaborative piece of work. Gareth Stedman Jones is right to point out that

a number of bones and indelible Marxist propositions beginning surface in Engels'due south rather than Marx's early writings: the shifting focus from competition to product; the revolutionary novelty of modern industry marked by its crises of overproduction and its constant reproduction of a reserve army of labour; the embryo at least of the argument that the bourgeoisie produces its own gravediggers and that communism represents, not a philosophical principle, just "the real movement which abolishes the present land of things"; the historical delineation of the formation of the proletariat into a class; the differentiation betwixt "proletarian socialism"; and small-principal or lower-center-class radicalism; and the characterisation of the land as an musical instrument of oppression in the hands of the ruling propertied course.84

This is an incredibly impressive list by whatsoever mensurate. Nonetheless information technology does non tell the whole story. Across Engels's codiscovery of the working class equally a potential revolutionary agent of change, he was the start socialist to recognize the importance of trade spousal relationship struggle to the socialist project. He besides laid the foundations for a historical understanding of the emergence of women's oppression and a unitary theory of its capitalist class. Alongside Marx, in The German Ideology, Engels elaborated a materialist conception of history through a synthesis of the idea of practice with a historical conception of material interest, and shortly thereafter he penned the start work of "Marxist" history—instigating an immensely productive and influential tradition.85 In his drafts of what became The Communist Manifesto, he applied the general perspective outlined in The German Ideology to the specific context of Germany in 1847, formulating a deeply democratic conception of socialism as a necessarily international movement—which incidentally showed that at its inception Marxism precluded Stalin's notion of socialism in one country. Furthermore, against the dominant socialist voices of his twenty-four hour period, Engels recognized that the struggle for socialism was not a zilch-sum game. He insisted that socialists should support conservative democratic movements while maintaining the political independence of the workers' political party with a view to challenging the bourgeoisie for power immediately upon the defeat of authoritarianism. He deepened this theory of "revolution in permanence" through his interest in the revolutions of 1848 when, aslope Marx, he played a primal role as a announcer in raising the general strategic analysis outlined in The Communist Manifesto to the level of do: extending, deepening, and shifting their perspective along the way.86 Subsequently, he played a office in the military struggle against Prussian absolutism. And afterwards the defeat of this movement, he focused much of his intellectual energies on developing a materialist analysis of military ability—and in so doing, "the General," as he became known in the Marx household, became one of the nineteenth century'southward greatest military thinkers.87 Though it has often been dismissed as a mere eccentricity, Engels'due south military machine writings were of the kickoff importance to nineteenth-century revolutionary strategy and remain of interest to modernistic socialists despite the significance of changes to military machine power over the succeeding century.88

Possibly most importantly, Engels as well won generations of socialists over to Marxism through his popularization of the Marxist method. And forth with his own and his collaborative works, he also prepared the 2d and third volumes of Marx's Uppercase for publication—and though modern scholarship has picked holes in this project, he nonetheless performed a Herculean task in presenting these manuscripts as coherently as possible. The left has benefited enormously from his efforts.89

At that place were, of course, numerous bug with Engels's contribution to the Marxist project: on reformism, value theory, nationalism, and the task of formulating a unitary theory of women's oppression, amidst other contributions, his thought suffered from important gaps and outright errors. Simply it would be incorrect, indeed gravely then, to allow these weaknesses to cloud our judgment of Engels's contribution to Marxism.xc What Lenin once said of Rosa Luxemburg might equally be said of Engels: "eagles may at times fly lower than hens, simply hens can never ascension to the superlative of eagles." Luxemburg, like whatsoever truly original thinker, made of import theoretical and political mistakes, withal she was an intellectual and political eagle.91 Similarly, any his weakness, Engels was an intellectual and political eagle whose writings remain of the showtime importance to those of us on the contemporary revolutionary left whose aim information technology is to avert the limitations of reformism without collapsing into sectarianism while simultaneously forging an upstanding and ecological socialism that escapes the moralistic "impotence in activity" of and then much mod leftist rhetoric.92

Notes

- ↩ Colin Barker et al., eds., Marxism and Social Movements (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 5, 14, 25.

- ↩ Norman Levine, The Tragic Deception: Marx Contra Engels (Oxford: Clio, 1975), fifteen, xvii; Frederic Bender, The Betrayal of Marx (New York: Harper, 1975), i–52; Terrell Carver, Engels (Oxford: Oxford Academy Printing, 1981); Terrell Carver, Marx and Engels: The Intellectual Relationship (Bloomington: Indiana University Printing, 1983); Terrell Carver, Friedrich Engels: His Life and Idea (London: Macmillan, 1989); Gregory Claeys, Marx and Marxism (London: Penguin, 2018), 219–28; Z. A. Jordan, The Evolution of Dialectical Materialism (London: Macmillan, 1967), 332–33; Sven-Eric Liedman, A World to Win: The Life and Works of Karl Marx (London: Verso, 2018), 497; Tom Rockmore, Marx's Dream (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 73; Jonathan Sperber, Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life (New York: Norton, 2013), 549–53; Gareth Stedman Jones, Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion (London: Penguin, 2016), 556–68; Paul Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism (London: Routledge, 2008), 35–49; Robert Tucker, Philosophy and Myth in Karl Marx (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961), 184; Andrzej Walicki, Marxism and the Jump to the Kingdom of Freedom (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), 121.

- ↩ H. Rigby, Engels and the Formation of Marxism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992), four; John Rees, ed., The Revolutionary Ideas of Frederick Engels (London: International Socialism, 1994).

- ↩ Paul Blackledge, "The New Left: Beyond Stalinism and Social Commonwealth?," in The Far Left in Britain Since 1956, ed. Evan Smith and Matthew Worley (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 45–61.

- ↩ George Lichtheim, Marxism (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964), 234–43.

- ↩ Donald Hodges, "Engels's Contribution to Marxism," Socialist Register (1965): 297.

- ↩ Alasdair MacIntyre, Marxism and Christianity (London: Duckworth, 1995), 95.

- ↩ Levine, The Tragic Deception, 15–16.

- ↩ Gustav Mayer, Friedrich Engels (London: Chapman & Hall, 1936), 224; Richard Adamiak, "Marx, Engels, and Dühring," Journal of the History of Ideas 35, no. 1 (1974): 98–112.

- ↩ Hal Draper, Karl Marx'southward Theory of Revolution, vol. 1 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977), 24.

- ↩ John Holloway, Change the World without Taking Power (London: Pluto, 2010), 121.

- ↩ Holloway, Change the Earth without Taking Power, 119; Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism, 39.

- ↩ Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism, 9, 43.

- ↩ Carver, Marx and Engels, 157.

- ↩ Carver, Engels, 76; see, by way of comparison, Carver, Marx and Engels, 129–xxx; Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism, 48.

- ↩ Carver, Engels, 48; Carver, Marx and Engels, 97; see, past fashion of comparison, Rockmore, Marx's Dream, 79.

- ↩ Carver, Marx and Engels, 116.

- ↩ John Green, Engels: A Revolutionary Life (London: Artery, 2008), 313; John Stanley and Ernest Zimmerman, "On the Alleged Differences between Marx and Engels," Political Studies 32 (1984): 227.

- ↩ I. Lenin, "The 3 Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism," in Collected Works, vol. fifteen (Moscow: Progress, 1963), 24; Paul Blackledge, "Hegemony and Intervention," Scientific discipline and Society 82, no. four: 479–99.

- ↩ Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Nerveless Works, vol. 25 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1975–2004), 120.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 25, 120.

- ↩ Paul Blackledge, "Practical Materialism: Engels'south Anti-Dühring as Marxist Philosophy," Critique 47, no. 4 (2017): 483–99.

- ↩ Terrell Carver, The Postmodern Marx (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), 173–74; Carver, Marx and Engels, xviii.

- ↩ Carver, The Postmodern Marx, 161–72; Carver, Marx and Engels; 2010; Terrell Carver and Daniel Blank, eds., Marx and Engels'south "High german Ideology" Manuscripts (London: Palgrave, 2014), 2; Rockmore, Marx's Dream, 96.

- ↩ Sebastiano Timpanaro, On Materialism (London: Verso, 1975), 77.

- ↩ Rigby, Engels and the Formation of Marxism, 4, 8.

- ↩ Dill Hunley, The Life and Idea of Friedrich Engels (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 64, 126.

- ↩ Heinrich Gemkov et al., Frederick Engels: A Biography (Dresden: Verlag im Bild, 1972), half-dozen; Fifty. F. Ilyichov et al., Frederick Engels: A Biography (Moscow: Progress, 1974), ten; Yevgenia Stepanova, Engels: A Short Biography(Moscow: Progress, 1985), 45–79.

- ↩ Draper, Karl Marx'southward Theory of Revolution, vol. one, 23.

- ↩ Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist Country (London: Verso, 1974), 23.

- ↩ Hunley, The Life and Thought of Friedrich Engels, 127–43.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 38, 505; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 45, 60–66.

- ↩ Carver, The Postmodern Marx, 165.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 40, 63–64.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 29, 264.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 41, 215; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 39, 391.

- ↩ Eleanor Marx-Aveling, "Frederick Engels," in Reminiscences of Marx and Engels (Moscow: Progress, north.d.), 187, 189.

- ↩ Paul Lafargue, "Reminiscences of Engels," in Reminiscences of Marx and Engels, 89–xc.

- ↩ Chris Arthur, introduction to The High german Ideology: Pupil Edition, past Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, ed. Chris Arthur (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1970), xiv.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Nerveless Works, vol. 17, 114.

- ↩ Draper, Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, vol. 1, 23.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 45, 288.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 45, 411–14; encounter, by fashion of comparison, Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 45, 392–94.

- ↩ Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism, 39.

- ↩ Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism, iii

- ↩ Hunley, The Life and Idea of Friedrich Engels, 145.

- ↩ Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism, ane–8; Carver, The Postmodern Marx, 111–12.

- ↩ Rockmore, Marx'due south Dream, 4.

- ↩ Carver, The Postmodern Marx, 111–12.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Nerveless Works, vol. 47, 202.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 26, 382.

- ↩ Moses Hess quoted in Francis Wheen, Karl Marx (London: 4th Estate, 1999), 36–37.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 41, 546.

- ↩ Alvin Gouldner, The Ii Marxisms (London: Macmillan, 1980), 283.

- ↩ Gouldner, The 2 Marxisms, 252.

- ↩ Edward Thompson, The Poverty of Theory and Other Essays (London: Merlin, 1978), 69.

- ↩ Hunley, The Life and Thought of Friedrich Engels, 55, 61.

- ↩ Chris Arthur, "Engels as Interpreter of Marx'southward Economics," in Engels Today, ed. Chris Arthur (London: Macmillan, 1996), 175.

- ↩ Carver, Engels, 74; Thomas, Marxism and Scientific Socialism, 4.

- ↩ Carver, Marx and Engels, 97.

- ↩ Andrew Evans, Soviet Marxism-Leninism (Westport: Praeger, 1993), 32, 39–40, 48, 52; Marking Sandle, A Brusque History of Soviet Socialism (London: UCL Press, 1999), 198–199; Mark Sandle, "Soviet and Eastern Bloc Marxism," in Twentieth-Century Marxism, ed. Daryl Glaser and David Walker (London: Routledge, 2007), 61–67; Herbert Marcuse, Soviet Marxism (London: Penguin, 1958).

- ↩ Evans, Soviet Marxism-Leninism, 52; Sandle 2007, 67.

- ↩ Herbert Marcuse, Soviet Marxism (London: Penguin, 1971), 102–103; Paul Blackledge, Reflection on the Marxist Theory of History (Manchester: Manchester University Printing, 2006), 78, 97, 110.

- ↩ Marcuse, Soviet Marxism, 128; Ethan Pollock, Stalin and the Soviet Science Wars (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 172–73, 182.

- ↩ Tristram Hunt, Marx's General (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2009), 361–62; Tony Cliff, Land Commercialism in Russia (London: Pluto, 1974), 165; Marx and Engels, Nerveless Works, vol. 25, 266.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Richard York, The Ecological Rift (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010), 218.

- ↩ Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness (London: Merlin, 1971), 3, 24n6.

- ↩ Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, 207.

- ↩ John Rees, introduction to A Defense force of History and Class Consciousness Tailism and the Dialectic, past Georg Lukács (London: Verso, 2000), 19–21.

- ↩ Georg Lukács, A Defence of History and Class Consciousness Tailism and the Dialectic (London: Verso, 2000), 102.

- ↩ Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1971), 448; see, past manner of comparison, Karl Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy (London: New Left Books, 1970), 122; Georg Lukács, The Ontology of Social Being: Marx (London: New Left Books, 1978), seven.

- ↩ Foster, Clark, and York, The Ecological Rift, 226.

- ↩ Foster, Clark, and York, The Ecological Rift, 226.

- ↩ Foster, Clark, and York, The Ecological Rift, 215–47.

- ↩ Foster, Clark, and York, The Ecological Rift, 240, 245.

- ↩ Karl Korsch, Karl Marx (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 77.

- ↩ Carver, The Postmodern Marx, 106; Levine, The Tragic Deception, 117; Carver and Bare, eds., Marx and Engels's "German Ideology" Manuscripts, 140.

- ↩ Carver and Blank, eds., Marx and Engels'south "German Ideology" Manuscripts, vii.

- ↩ Carver, Marx and Engels, 71.

- ↩ Arthur, introduction to The German language Credo: Student Edition, 21; Chris Arthur, "Marx and Engels's 'German Credo' Manuscripts: Presentation and Assay of the 'Feuerbach Chapter,' A Political History of the Editions of Marx and Engels'southward 'German Credo' Manuscripts reviewed by Chris Arthur," Marx and Philosophy, May 22, 2015.

- ↩ Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution (London: Abacus, 1962), 366.

- ↩ I. Lenin, "Against Boycott," in Nerveless Works, vol. xiii (Moscow: Progress, 1962), 37.

- ↩ Thompson, The Poverty of Theory and Other Essays, 69.

- ↩ Gareth Stedman Jones, "Engels and the Genesis of Marxism," New Left Review 106 (1977): 102; Gareth Stedman Jones, "Engels and the History of Marxism," in The History of Marxism, ed. Eric Hobsbawm (Brighton: Harvester, 1982), 317; see, by fashion of comparing, Tony Cliff, "Engels," in International Struggles and the Marxist Tradition (London: Bookmarks, 2001).

- ↩ Paul Blackledge, "Historical Materialism," in Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx, ed. Matt Vidal et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

- ↩ Paul Blackledge, "Engels'due south Politics: Strategy and Tactics after 1848," Socialism and Democracy 33, no. two (2019): 23–45.

- ↩ Hunley, The Life and Thought of Friedrich Engels, 21; Sigmund Neumann and Marking von Hagen, "Engels and Marx on Revolution, State of war, and the Regular army in Order," in Masters of Modern Strategy, ed. Peter Paret (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 265.

- ↩ Paul Blackledge, "War and Revolution: Friedrich Engels as a Military Thinker," War and Society 38, no. ii (2019): 81–97.

- ↩ Fred Moseley, introduction to Marx's Economic Manuscripts 1864–1865 (Leiden: Brill, 2016).

- ↩ Paul Blackledge, "Engels, Social Reproduction and the Problem of a Unitary Theory of Women'southward Oppression," Social Theory and Practice 44, no. 3 (2018): 297–321.

- ↩ I. Lenin, "Notes of a Publicist," in Collected Works, vol. 33 (Moscow: Progress, 1996), 210.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 4, 201; Marx and Engels, Nerveless Works, vol. 5, 11; Paul Blackledge, Friedrich Engels's Contribution to Modern Social and Political Thought (New York: SUNY Press, 2019).

Source: https://monthlyreview.org/2020/05/01/engels-vs-marx-two-hundred-years-of-frederick-engels/

Enregistrer un commentaire for "The Political Ideas of Marx and Engels Review"